Published in Horses and People Magazine & Hoofbeats Magazine

Its all about healthy soil

By Mariette van den Berg, BAppSc. (Hons), MSc. (Equine Nutrition)

Horses compact ground, and they especially love to do so in the corners of paddocks. But when soils are compacted by hoofed animals, rainwater is unable to penetrate the ground to the compaction layer and grass roots cannot open up the soil.(1) By means of property design, using permaculture and Keyline principles and strategies, we can actively hydrate the land, build soil, and regenerate horse pastures.

Compaction & erosion on horse properties

How to de-compact soil?

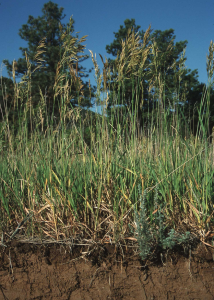

Extremely compacted grounds are impossible to de-compact naturally unless we use weeds to do the hard work for us. As we describe in previous section, weeds with deep, thick tap-roots can only grow in hard, compacted soils, and we can use these to fast-track our pasture management and build soil.(2,3)

Extremely compacted grounds are impossible to de-compact naturally unless we use weeds to do the hard work for us. As we describe in previous section, weeds with deep, thick tap-roots can only grow in hard, compacted soils, and we can use these to fast-track our pasture management and build soil.(2,3)

If paddocks are slashed before the weeds seed, the weeds die. The roots in the ground also die and break down, allowing air and moisture to penetrate deeply and adding organic matter high in minerals to the soil. This process can be repeated several times. Many weeds adapt themselves to growing in poor soil and accumulate the very minerals that the soil is lacking.(2) Therefore, it is important to instigate a system using weeds. Once the soil biology and minerals are restored, weeds are ‘out-competed’ by grasses, because the weeds cannot grow in nutrient-dense soil.

A fast way to de-compact and regenerate horse pastures and paddocks is by using Keyline design and mechanical methods such as Yeomans Keyline Plow or a Wallace Plow to deep-rip (not cultivate) the pasture with a chisel plough shank that slices, lifts the soil, and closes after the pass of the plod (see figure 1). The Yeomans Keyline Plow utilises a special cultivation technique to infiltrate water into the soil efficiently and hold it on the land as long as possible.(4) It’s almost as though the ground is able to take a deep breath, allowing moisture and oxygen in

Figure 1. Soil development – mechanical method (Illustration adapted from the

Permaculture; A Designers’ Manual).

The first shallow rip with the Keyline Plow allows roots to break through the first compaction layer. Second season, the pass goes deeper again and the roots follow. The final pass is to a depth of approximately 24 inches (600 mm). Grasses can now start to work with soil bacteria and fungi to access deep minerals, which are essential for grazing animals. Over three to four passes with the Yeomans Keyline Plow, and using Keyline Design, we can de-compact soil, increase soil carbon, build soil, increase water-holding capacity, increase soil life in the soil food web, and even drought-proof our land.

What is Keyline® Design?

The Keyline design and plough concept was originally developed by P.A. Yeomans in the 1950s to address issues of dwindling water supplies and soil erosion on Australian rangeland.(4) Yeoman developed a system of ‘amplified contour ripping’ that maximises productive use of rainfall and facilitates the uniform irrigation of land. Keyline is a philosophy and technique that regenerates rural and urban landscapes, supports the protection of wildlife and fish habitats, and (with carbon sequestering techniques) helps to address aspects of global warming and climate change. Keyline principles and techniques are based on a holistic approach that works with natural patterns to restore and increase the depth and fertility of the soil, while increasing its water-holding capabilities.

The term Keyline comes from the reference to a ‘keypoint’ on the watershed, which is the interface between collection and distribution of water on the landscape — where ridge meets the valley (figure 2). Keyline planning is based on the natural topography of the land. It uses the form and shape of the land to determine the layout and position of farm dams, irrigation areas, roads, fences, farm buildings, and tree lines. Keyline layouts of farm and grazing lands also incorporate design of the storage of run-off water within the farm. A good design efficiently spreads the often-irregular rainfall patterns so common to Australia and enhances rural production even on the smallest of horse properties.

Figure 2: A keypoint is the point on a slope cross-section where the slope transitions from convex to concave, where the convex ridge characterized by high erosion gives way to the depositional concave slope. Keypoints are often characterized by the beginning of a discernable channel, where subsurface flow from higher in the slope surfaces, in effect like the end of a pipe, and can be effectively captured and redistributed. A keyline is the contour line that intersects with the keypoint. As opposed to contour lines which often vary in distance along their length, keylines fall off contour at the same elevation along the length of the line such that keylines are always parallel to each other, making the creation of keyline cuts particularly amenable to mechanical management using a tractor and plow. Contour intervals are drawn in from the 130-foot line to the 260-foot line (www.yeomansplow.com.au)

Keyline concepts are the opposite of conventional practices of farm design. Conventional horse property design creates an artificial and dangerous practice of concentrating run-off water into manufactured disposal drains designed to remove, as rapidly as possible, run-off water from a rural landscape, i.e. a rapid evacuation of rainwater to the nearest creek or lake that ends up in the ocean. In Australia, the driest of the world’s continents, this is counterintuitive. This practice can, and often does, create more erosion than it was ever intended to prevent. On these horse properties, paddocks frequently turn into mud-pits, following long periods of mismanagement. Compaction of the soil by horses stops water from penetrating the ground to the compaction layer and stops grass roots from opening up the soil and de-compacting naturally. Also, the removal of trees from the pasture eliminates the natural cycling and storage of water by the trees, which we describe in more detail in following chapters. Re-patterning and Keyline concepts can help property managers halt erosion and improve pasture hydration. Keyline design has a wide range of applications from the smallest acreage through to larger farms.

Improving soil carbon and water harvesting

The previous section mentions strategies and methods, such as Keyline design and Yeomans Keyline ploughing, to create soil, harvest water, and to drought-proof and de-compact our pastures and paddocks. The next concept we highlight is soil creation and water harvesting.

Soil carbon

As a result of our farming and land management practices, global soil carbon levels have significantly dropped. Conversion of natural to agricultural ecosystems causes depletion of the soil organic carbon pool by as much as 60% in soils of temperate regions and 75% or more in cultivated soils of the tropics.(5) Depletion is exacerbated when the output of soil carbon exceeds the input and when soil degradation is severe.

As a result of our farming and land management practices, global soil carbon levels have significantly dropped. Conversion of natural to agricultural ecosystems causes depletion of the soil organic carbon pool by as much as 60% in soils of temperate regions and 75% or more in cultivated soils of the tropics.(5) Depletion is exacerbated when the output of soil carbon exceeds the input and when soil degradation is severe.

Soil carbon is important because it acts like a sponge — holding water and nutrients — and supporting life for organisms above and below the surface. So much of human settlement is built on compacted run-off land, whether it be roads, overgrazed farm land, or the suburbs or cities we call home. Still, water has to go somewhere. If it is not into soil carbon for storage and hydration, then it is out to sea. Rather than washing away the topsoil of a compacted landscape, Keyline design slows the effects of changing weather patterns and better allows the landscape to absorb changes as they arise.

Keyline systems positively contribute to erosion control by building soil and soil carbon. Through the process of deep-ripping land and moving water from gullies to ridges to hydrate the landscape, Keyline systems help to drought-proof farms by encouraging deep penetration of plant and grass roots. Proponents of Keyline design do not believe that soil creation must be a slow process or that soil once lost is lost forever. Keyline practices effectively eliminate soil erosion; in fact, soil fertility, and even soil itself, can often be created faster than it can be eroded.

Water harvesting

The main idea behind Keyline design is to capture water at the highest possible elevation and comb it outward toward the ridges using gravitational forces, reversing the natural concentration of water in valleys.(4) Maximising the flow of water to the drier ridges and using precise plough lines that fall slightly off contour slows the movement of water and spreads it more uniformly, infiltrating it across the broadest possible area (figure 3). By effectively capturing and distributing rainwater and enhancing soils, Keyline design allows us to delay irrigation from off-farm sources until later in the season, and can result in fewer applications being required in the dry season.

Figure 3. Keyline cultivation. (Illustration adapted from Yeomans Keyline Plan (4).

This system captures significant quantities of water that would otherwise run off, and stores it in the soil. It also builds soil fertility, which further improves moisture-holding capacity. The addition of organic matter increases the number of micropores and macropores in the soil — either by ‘gluing’ soil particles together or by creating favourable living conditions for soil organisms.(6) Certain types of soil organic matter can hold up to twenty times their weight in water.

The result of Keyline cultivation is an overall drift of surface run-off water, which prevents run-off concentration and the resultant gully erosion. It increases the time of contact between the rain and the earth and has the effect of turning storms into steady soaking rain. Rain may have become less frequent in some parts of Australia, but its intensity and volume over a twenty-four-hour period is growing.

By capturing and retaining water, Keyline systems also help to control flooding.(4) The net effect of a Keyline system is to flatten hydrograph peaks, which both reduces flooding during storm events by storing more water in the soil and dams, and allows stored water to seep back into waterways over a much longer period. Keyline design can lengthen the run of seasonal creeks, augmenting supply in drier summer months and improving the quality of water that is returned from farms to waterways. Keyline design can also contribute to groundwater recharge, improving the health of wells and, in particular, increasing water security in alluvial valleys.

While Keyline designs are based on the topography and geology of the land, individual properties are shaped by the historic location of survey lines, and such lines generally bear no relationship whatsoever to topographical land forms. In consequence, idealised Keyline systems can be hampered somewhat by the constraints of farm boundaries. Cooperation between land owners is necessary to eliminate as many design constraints as possible, but the payoff is generous: most land owners can expect sizeable economic savings and improved viability for water harvesting and storage systems that otherwise could not exist.

The implementation of Keyline plans on multiple farms in a given catchment area can significantly benefit the health of the watershed as a whole.(4) Coupled with correct cultivation and soil development techniques to enhance biological activity, this can, in turn, rapidly increase the fertility of all soils.

Soil development and management

Soil life responds dramatically to ideal air, moisture, food, and temperature conditions. These conditions are simple to create with grazing, sub-soiling, and dependable rainfall or irrigation. Life begets life. Plants, their roots, and attendant exudates are the solar harvesters and the raw food for soil life.

Grazing animals are ‘biological accelerators’ in that they are the most effective tools to be used to speed mineral cycling: grazers affect enough land to make a significant impact.1 Grazing animals can build topsoil surprisingly quickly; however, merely keeping a number of horses in a paddock and not managing the space properly only makes soils worse. We must take time and care to actively manage animals in order to restore degraded landscapes. We discuss holistic animal management in the grazing planning section.

Further reading:

- Savory, A. & Butterfield, J. 1999. Holistic Management: A new Framework for Decision Making. 2nd edition. Island Press, Washington, DC, USA.

- Pfeiffer, E. E. 2012. Weeds and What They Tell. 3rd edition. Biodynamic Farming and Gardening Association, Springfield, IL, USA.

- Mollison, B. 2011. Introduction to Permaculture. 2nd edition. Tagari Publications, Australia.

- Yeomans, P.A. 2008. Water For Every Farm: Yeomans Keyline Plan. 4th edition. Keyline Designs, Australia (www.keyline.com.au).

- Lal, R. 2004. Climate Change and Food Security: Soil Carbon Sequestration Impacts on Global Change and Food Security. Science 304; 1623–1627.

- Bot, A. & Benites, J. 2005. The Importance of Soil Organic Matter: Key to Drought-resistant Soil and Sustained Food Production. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome.